I recently delivered a short talk as part of our whole school INSET on effective feedback. In my section, I talked specifically about how to use misconceptions and common errors to provide whole-class feedback.

In this post I will outline the points I made to explain this with some examples for Physics and Sociology. Both of the examples were from Key Stage 5 (Year 12) but the principles are applicable to any Key Stage.

At the bottom of the page, there is a list of suggestions for follow-up tasks to complete based on feedback, as well as a checklist for effective whole-class feedback.

Why whole-class feedback?

The reason I focused on whole-class feedback rather than individualised feedback (e.g. book marking or comments for each pupil) is mainly for sustainability. There are only so many problems that can come up in an assessment and so, when I did have to give individualised comments as a trainee, I was writing the same things over and over.

What kind of feedback do I need to provide?

There are three types of feedback a student might need:

- Feedback on silly mistakes – generally not much feedback is required here

- Feedback for lack of knowledge or understanding – this might require students to go and learn something themselves and practise a bit more, or perhaps sometimes some supplemental teaching

- Feedback for misconceptions – whilst supplemental teaching is likely here, the task design needs to both break down the incorrect model students have built in their long-term memory as well as force the deliberate practice to build up new, correct knowledge / models.

Regardless of the type of feedback students are acting on (and the action on feedback is the most important part, I think), the follow-up tasks need to be applicable to new scenarios and problems and contexts.

The process of designing the tasks

- Whilst marking, make notes on the mark scheme (or somewhere else, e.g. I use OneNote or a Word document) about the issues I’m seeing crop up. These can be related to standard of literacy, answer structure, substantive knowledge, disciplinary knowledge, misconceptions or even just silly mistakes.

- I’ll use the notes I’ve made to write an ‘examiner’s report’, just like the exam boards. Sometimes, the exam-board provided examiner’s report is hugely helpful. Other times, I’ll add my own analytical comments. Sometimes both.

- Once I’ve written up the report (which takes far less time than you’d think), I can then decide on follow-up tasks for students to work on. I’ll explain more on this later in the post.

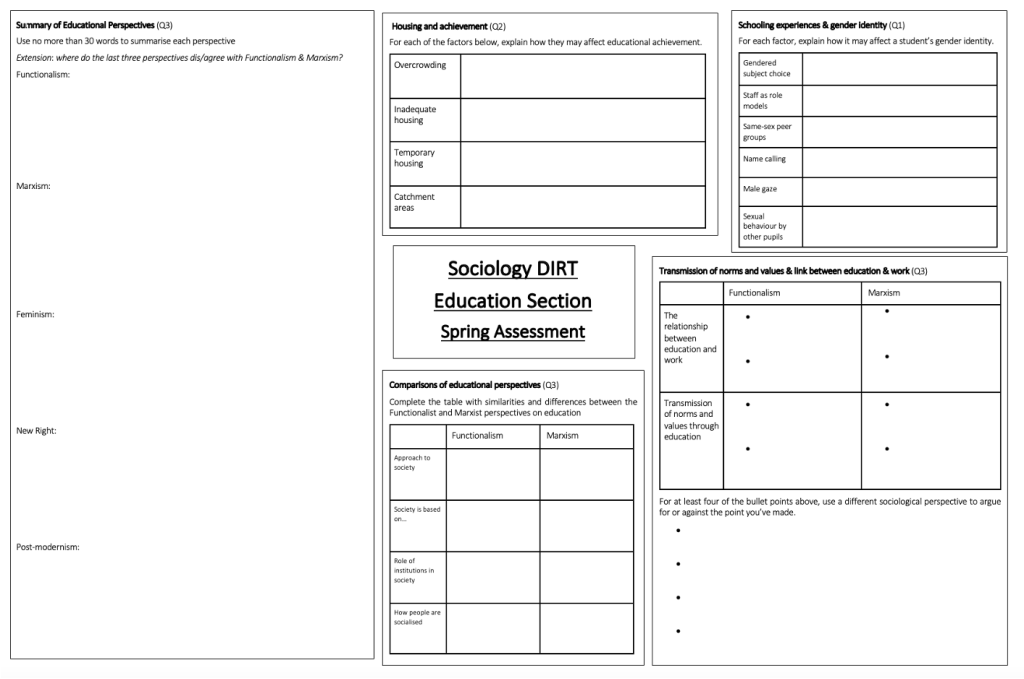

Example 1: Year 12 (A-level) Sociology

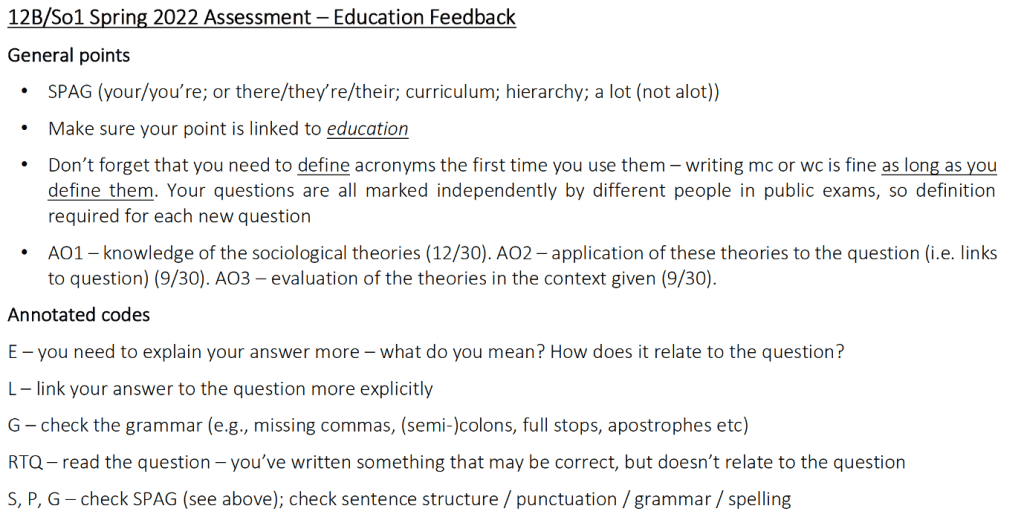

This first image shows some very general feedback across an entire assessment. This includes ensuring that students are focusing on the right topic, literacy, use of acronyms, what my marking codes mean, and what the point of the Assessment Objectives is.

Students need to: check through everything they’ve written for these issues, identify them, and correct them.

This second part (from the same feedback sheet / ‘examiner’s report’) gives the feedback for the third and final question, a 30-mark essay. Here there are comments based on what I read in all of the answers. Again, this is based on the notes I made whilst marking. We have covered things like ‘what makes a comment evaluative’ and ‘identifying hooks’ in lessons, so students should be familiar with these ideas.

Students need to: check their answer for the issues mentioned. They can work with peers if needed to identify the issues in their own writing.

This is the example marking rubric given back to each pupil. Rather than writing individual comments, I will have ticked in the relevant boxes so students know how they’ve done with each aspect of their essay.

Students need to: (if they’ve scored less than about 75% of the available marks) choose a paragraph to re-write, and make clear the changes they have made and why. For some students, they may need to identify how they would re-order the points they have made to build a better thread through the essay but without re-writing the whole thing.

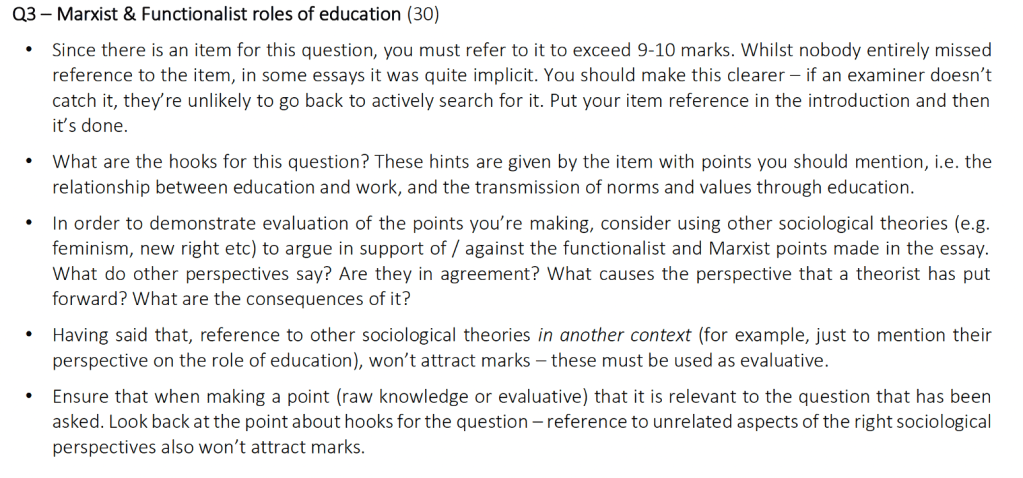

Whilst these are all helpful for points 1 and 2 in the list above, students then need follow-up tasks. They then received the below A3 sheet:

Here, I have designed the tasks to match up with the feedback. Some tasks address gaps in substantive knowledge (e.g. names of theorists, key quotes or concepts). However some boxes force active comparison of different sociological theories in order to aid in their evaluation.

Students need to: complete the box for each question they lost more than 25% of the marks on.

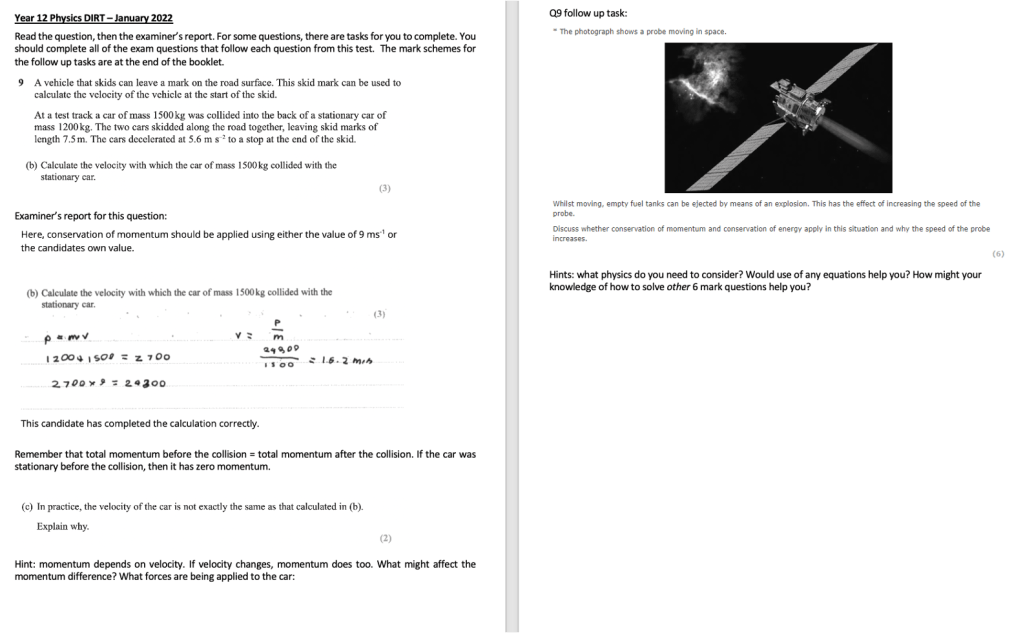

Example 2: Year 12 (A-level) Physics

These two pages are the first of a multi-page booklet students received, once I’d verbally addressed some common issues the whole class needed. Again, I decided what to talk to the group about, and what to include in this booklet, using the notes I made whilst marking.

On the left-hand page, there is the original question the students were asked. I have included both the exam report from the exam board, as well as added comments based on what I read in student answers.

The right-hand page then shows the follow-up task. The aim here is that the feedback they’ve received via the report on the first page, which is specific to the question they answered, is now applied to a new question. The knowledge they need is the same, but there is a new need for application of that knowledge.

Students need to: read the exam report for each question they lost marks on, and use it to correct their answers. I also usually ask students to write a note to themselves about why the correction is better to aid their future self-regulation and metacognitive thinking. Then, they need to complete the relevant follow up task. A mark scheme is provided for the follow-up task, so students can self-mark.

Ideas for follow-up tasks

- Raw corrections – literally adding corrections to their answers. Best for silly mistakes or gaps in knowledge.

- Short recall questions (“torture tests”) – self explanatory. Best for gaps in knowledge.

- Additional practice – practice questions where students are applying their corrections to a new context (see the Physics examples). Best for misconceptions and gaps in knowledge.

- Redrafting answers – considering what went wrong in the first place, and re-doing that answer. Best for misconceptions.

- Self-evaluation: identify changes made & why. Best for misconceptions.

Checklist for effective feedback

- Is the problem ‘further upstream’? Consider whether the task set was appropriate and that the original delivery of the knowledge (and the students’ practise applying that knowledge) was successful.

- Is the feedback focused on a specific part of the work? If it’s too general, it can’t be applied to new scenarios very easily.

- Is the feedback for the specific task linked to developing self-regulation and general understanding? If it’s too specific, it won’t be applicable to other tasks – students need to be able to transfer their new skill to new problems.

- Are students acting on the feedback? If they’re not, what was the point?

TL;DR

If feedback is to be timely, specific, and fruitful then students need to be receiving specific feedback that is applicable to new problems then the task design following the provision of feedback is paramount, and needs to link to their ability to self-regulate (i.e. think metacognitively) throughout the process of answering questions and solving problems.

References

- Fletcher-Wood (2018) Responsive Teaching: Cognitive Science & Formative Assessment in Practice

- Black & Wiliam (1998) Inside the Black Box – aim for success, focused, specific

- Brown, Race & Smith (1996) Ten-Point Assessment Manifesto – consistently used & built into the curriculum

- Gould & Roffey-Barentsen (2018) Six Stages of Feedback – record the targets, what they involve, and give a time frame for completion

- Shute (1987) Assessing Students: How Shall We Know Them? – task-focused, not learner-focused

Leave a comment