Sometimes I’m reminded (either through Twitter, day-to-day conversation, or another way) that a fair few teachers don’t see much (any) value in the use of educational research. Whilst it is true that a lot of it is very contextual, I don’t agree that it can’t be helpful. What is unhelpful is educational research that is so inaccessible to teachers that it won’t ever actually do anything for practitioners.

In this post, I’m aiming to outline what self-determination theory (SDT) is all about. Whilst the focus of the theory is to explain why some students are motivated, and how they are motivated, I believe that it can be helpful in the classroom on a basic level too.

I’ll give a brief overview of where SDT comes from and what it means, and then I’ll talk about how it might help classroom practice. At the end are some references for papers that might be of interest. This post was inspired by a previous post, where I outlined the research I’ll be conducting over the next few years in relation to this theory.

What is SDT?

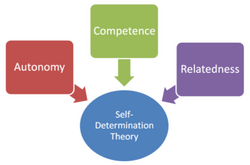

In a nutshell, this theory (first proposed by Ryan and Deci (see some references below)) outlines that someone will need to feel autonomy, competence, and relatedness in order to be self-determining. Autonomy, since they are in control of their own path; competence, since they’ll need to feel like they’re actually capable of doing the task; and relatedness to others, so they don’t feel alone in their experience.

Students may experience additional autonomy if they are aware of their own goals (and why they’re pursuing those goals); having identified or internalised extrinsic goals means that those goals are fundamental to their motivation.

Achieving a feeling of competence in the students can be more challenging. This can occur in two main ways that I can see. Firstly, if students are actually achieving something e.g. test scores, then they necessarily must be competent (at least to some extent). The second of these, which I’ll talk more about shortly, is the use of positive language from teachers/educators such that the student feels that the adult thinks they’re capable.

A paper by Soenens et al. (2012) showed that when teachers use ‘psychologically controlling language’, students experience an increase in controlled motivation (i.e. less autonomy), and will feel less competent. The difference between “you can do even better than this next time” and “this attempt isn’t really good enough” is huge. The former indicates that there is improvement to be had, but indicates to a far lesser extent that a student has underperformed, or let you down, like the latter statement does. That’s not to say that the second statement doesn’t have a place, but it’s far less positive and the kind of statement I try to refrain from where possible.

Practical tips for the classroom

There are practical things practitioners can do in the classroom that might help here. I don’t think they’re particularly complex, but they might make a significant difference.

I’m not going to talk about how the most SDT-y thing we could do is spend more time fostering an intrinsic love of learning our subjects, because that is incredibly difficult. This is made so difficult firstly by teachers’ lack of free time outside of lessons to develop lessons that work toward this to a larger extent, as well as a lack of time in lessons due to a large curriculum, and a lack of time to cover it.

The first of these is to introduce any autonomy possible for students so that they feel that they’re in control of what they’re doing. For example, during revision / DIRT lessons (which I’ll write about another time), giving students a range of tasks that they can work through in whatever order they like.

Notice here that students are still doing the same overall task, but they’re allowed more control over how they go about that task. Maybe you’re letting them choose from a few different tasks, but they don’t have to do all of them: student choice. In a more ‘normal’ lesson, if the task is focused around a new concept, maybe the question set is ramped in difficulty and students can start on Easy or Medium, depending on how they feel. As long as they have some more choice, you’re golden.

Students may also benefit from some collaboration. Whilst this isn’t a call to let students chat during their work (which inevitably won’t help), students asking each other for help in a teamwork-like environment is helpful.

Perhaps most crucially, the language we use with students can have a huge impact. Whilst sometimes negative language helps to articulate an issue with a student, the more positive the better. This doesn’t mean “oh don’t worry about not doing your homework, I’m still proud of you!”. Not at all. What it does mean is when a student has genuinely tried at something, praise that, and talk about how the student can progress to meet your standards.

Even if the score is poor, if they’ve tried hard then that’s worth praising. Any indication you can give a pupil that you think they’re even vaguely competent will help their self-esteem, and thus their motivation. Bureau et al (2021) reckon that competence is the most important of these aspects (trumping autonomy and relatedness), when considering the extent to which a student is self-determining in their motivation.

It all makes sense really – I’d much rather do a task if I’m confident I’ll be successful at it.

Papers of interest (References)

Bureau, J. S., Howard, J. L., Chong, J. X. Y., & Guay, F. (2021). Pathways to Student Motivation: A Meta-Analysis of Antecedents of Autonomous and Controlled Motivations. Review of Educational Research. https://doi.org/10.3102/00346543211042426

Gagné, M. and Deci, E. L. (2005). Self-Determination Theory and Work Motivation. Journal of Organizational Behaviour, 26(4), 331-362.

Ryan, R. M. and Deci, E. L. (2000). Intrinsic and Extrinsic Motivations: Classic Definitions and New Directions. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 25, 54-67.

Soenens, B., Sierens, E., Vansteenkiste, M., Doochy, F. and Goossens, L. (2012). Psychologically Controlling Teaching: Examining Outcomes, Antecedents, and Mediators. Journal of Educational Psychology, 104(1), 108-120.

Leave a reply to Students’ views on competence and other factors affecting motivation – The Teacher-Researcher Cancel reply